It’s been ten years, remarkably, since Tyler Cowen published The Great Stagnation, a phenomenon of a Kindle Single which drew attention to, and sought to explain, a sustained slowdown in economic growth which began in the early 1970s. The book had a profound influence on my thinking. It moved me to write and publish my own Kindle Single in September of 2011: The Gated City, which examined how restrictions on urban growth harmed the economy by channelling people away from productive places. Its influence was there, too, in The Wealth of Humans, which considered how labor abundance contributed to institutional dysfunction and broader economic and social problems.

But after a decade of thinking about the era of stagnation I still find myself wondering if it wasn’t actually this or that other thing which really mattered most. And lately, I’ve found myself thinking about energy.

Paul Krugman considered the growth slowdown in a column written back in 1996. (It was, in hindsight, an amusingly timed piece. Krugman noted then that for all the wondrous new information technology sprouting around us, productivity growth remained stuck in a rut. We now know that 1996 marked the beginning of an eight-year surge in productivity rooted in IT advances. But we also know that while IT has only gotten better, that brief run of good, old-fashioned rapid growth was not to be sustained.)

At any rate, his piece is notable for introducing the kitchen test of technological advancement:

Better yet, think about how a typical middle-class family lives today compared with 40 years ago—and compare those changes with the progress that took place over the previous 40 years.

I happen to be an expert on some of those changes, because I live in a house with a late-50s-vintage kitchen, never remodelled. The nonself-defrosting refrigerator, and the gas range with its open pilot lights, are pretty depressing (anyone know a good contractor?)—but when all is said and done it is still a pretty functional kitchen. The 1957 owners didn't have a microwave, and we have gone from black and white broadcasts of Sid Caesar to off-color humor on The Comedy Channel, but basically they lived pretty much the way we do. Now turn the clock back another 39 years, to 1918—and you are in a world in which a horse-drawn wagon delivered blocks of ice to your icebox, a world not only without TV but without mass media of any kind (regularly scheduled radio entertainment began only in 1920). And of course back in 1918 nearly half of Americans still lived on farms, most without electricity and many without running water. By any reasonable standard, the change in how America lived between 1918 and 1957 was immensely greater than the change between 1957 and the present.

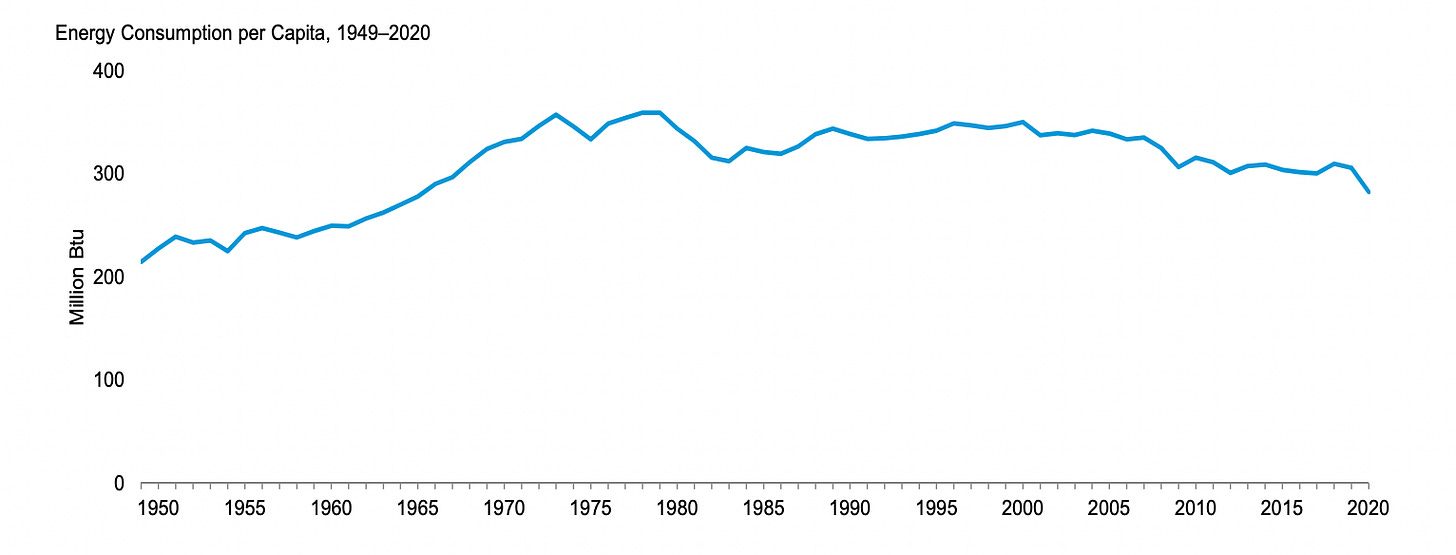

Comparisons like this (and others which are similar in spirit, like Peter Thiel’s quip that we were promised flying cars and instead got 140 characters) encourage us to focus on the quality and quantity of technological innovations. The problem they identify, in other words, is that we once discovered transformative new things but don’t any longer. But that strikes me as an incomplete description of what has actually happened. One might instead say that we used to find ways, often through new technologies, to harness ever more energy in the service of human welfare and comfort; now we don’t. Look again at the Krugman passage, and it’s obvious: the gas-ranges, electricity, the replacement of horse-drawn wagons. This distinction also stands out in the data. Here, for instance, is American energy consumption per capita since 1949.

Or take it back further in time:

Historically, at least, explosive growth in real incomes per person has been synonymous with explosive growth in energy consumption per person. This shouldn’t be surprising in the least! Energy, we are taught in school, is the capacity to do work. Sustained growth in incomes is about augmenting human labor, such that what can be produced, per person, increases over time. Economists usually describe this increase in terms of the amount of capital available per person (meaning things like equipment), or in terms of technological progress. But equipment does not run on its own! Wringing more food from the earth, or more clothing from weavers, or more and faster transport from the best available transport technology requires more energy input.

The role of energy is particularly clear when we think about the dazzling transformation of the physical world by new technologies: the speed with which we go from here to there, the illumination of our cities, the hum of home appliances. The difference between the sci-fi futures people imagined a half century ago and the present as we live it—similar to the past, but we all have pocket computers—is an energy gap. What’s more, scholars in the 1960s understood the energetic nature of progress very well; science-fiction authors often describe the sophistication of a civilization using the Kardashev scale, invented by a Russian astrophysicist in the 1960s, which characterizes a society’s level of technological advancement in terms of the amount of energy it utilizes.

Some economic historians have also made note of this. Pre-industrial societies relied on power provided by humans themselves and by animals, and on energy generated by firewood (or charcoal). Such things were constrained by what could be produced—in terms of food, feed and timber—on a finite supply of land. The exploitation of fossil fuels liberated society from these constraints, thus creating opportunities to produce more per person by developing technologies which could exploit the energy contained within those fossil fuels. Indeed, Robert Allen has argued that scarce labor and abundant coal in Britain (relative to rival economies) generated incentives to mechanize production which help account for its first-out-of-the-gate industrialization.

Increased energy use is essential to progress. Yet generally we do not speak in such terms today, for very good reasons. Since the 1960s we have learned how damaging fossil-fuel use can be. Extraction causes significant environmental damage. Burning fossil fuels creates harmful pollutants. Reliance on fossil fuels complicates geopolitics and is often a source of economic vulnerability. Perhaps most important, energy generated by burning fossil fuels changes the composition of the atmosphere and thus the climate. Anthropogenic climate change threatens to introduce new constraints on our ability to raise our living standards, and could potentially cause them to fall, perhaps by a lot.

So over the last half century, we have shifted priorities, from generating ever more energy per person to generating ever more economic output from a given energy input. (With notable exceptions; in fast-developing economies energy use has continued to grow explosively, as of course has output per person.) Now, please don’t get me wrong: energy efficiency is good. Making the most of what you have makes sense, particularly in a context in which what you have is both non-renewable and harmful when consumed in excess. I should also note that scarce, expensive energy can promote innovation. Efficiency-boosting invention is part of what we expect to happen in response to a carbon price (or a rise in the price of oil, say). Given the costs of climate change, promoting energy conservation is a better route to boosting long-run living standards than going full bore for increased energy production—in the absence of clean energy alternatives.

But crucially, if you manage to disentangle growth in energy use from growth in the negative consequences of fossil-fuel use, then you are back to a world in which the harnessing of ever-greater amounts of energy per person is associated with transformative economic change and rising living standards. We run the risk of convincing ourselves that increasing the amount of energy we consume is bad per se, which is a very silly thing to believe when we could make everyone on the planet much, much better off by increasing the fraction of the sun’s energy which we consume from a very, very, very tiny share to a share which is instead only very, very tiny. Indeed, it might be both politically useful and economically accurate to argue that investing heavily in sources of clean, abundant, cheap energy is critically important not only because it will help us in the fight against climate change, but because it is absolutely necessary to unlock the next great era of economic progress and increases in living standards.

It can be difficult today to see how abundant energy, “too cheap to meter”, might transform our lives. We have come to see energy-hogging applications of new technologies as inherently bad, and a growing number of us never lived during the era when rapid growth, awesome technological change and increased energy use all went hand-in-hand. It seems offensive to even imagine innovations which might make life more convenient by using vast amounts of energy, and imagining new technologies is always a little difficult anyway; people in the late 19th century would have struggled to anticipate how electrification of every home or the widespread use of the internal combustion engine would change their daily lives. Knowing what we know about climate change, working actively to increase energy use per person is not merely obscene; it is sociopathic.

But in many ways the most important distinction between modern society and pre-industrial life is in the amount of energy we consume per person; one could argue that all the rest of it—the scientific know-how, advanced technologies, complex institutions and so on—flows from that. If there is a grand human future ahead of us, in which more people live healthy lives of comfort, it is almost certain to require a significant increase in energy consumption per person. Or to return to The Great Stagnation1, the low-hanging fruit of which we partook so insatiably during the era of rapid growth included—or indeed, may have consisted mostly of—fossil fuels. Escaping it means putting that era behind us by developing sources of abundant, guilt-free energy. The sooner the better.

Cowen’s book is subtitled “How America Ate All The Low-Hanging Fruit of Modern History, Got Sick, and Will (Eventually) Feel Better”

Isn't this what economist and physicist Robert Ayres said, "The essential truth missing from economic education today is that energy is the stuff of the universe, that all matter is also a form of energy, and that the economic system is essentially a system for extracting, processing and transforming energy as resources into energy embodied in products and services. "

What this misses is that current increases in energy demand still result in increasing fossil fuel consumption AND the path to decarbonization is MUCH faster if the total energy required is kept in check. After decarbonization is mostly complete (2050 or later) then you can safely add as much energy demand as you want. But that process will be automatic because electricity prices should continue to fall as we create better grids.