Revenge of the robots

So there are plenty of jobs after all! For now.

Back in 2016 a book of mine came out, titled The Wealth of Humans. It’s kind of a funny little book, a bit all over the place, but its main idea is that the economy doesn’t really work the way we want it to when labor is abundant relative to other factors. A lot of the book looks backwards: noting, for example, that labor abundance in the decades prior to publication contributed to a structural decline in workers’ bargaining power, concentration of income in the hands of capital and the rich, and a subsequent problem of chronically inadequate demand. But it also engages in some speculation about the future.

In particular, it argues that labor abundance could become a permanent feature of the economic landscape. Given the book’s other arguments about how labor abundance causes elements of our economic and political structures to misfire, that eventuality would likely mean either that pretty fundamental features of the economy need to change, or that we become ensnared in one or another serious crisis. The book posited a labor trilemma: in which labor markets are unlikely ever again to generate work which provides mass employment, pays good wages, and isn’t very susceptible to automation. We will manage at most two of those three.

Well and now here we find ourselves with circumstances having changed somewhat. One thing which is interesting to reflect on is how it was that we got from that world of abundant labor, described by the book, to this one, in which no one can seem to find people to fill open jobs. There are various stories—which Ben Casselman does a nice job working through here—about why workers have become choosier about work. But the heart of the matter is that pandemic-relief measures placed a vast amount of purchasing power in the hands of the non-rich, thus striking directly at the heart of the macroeconomic malaise America has experienced over the past few decades. Demand surged as a consequence, which contributed to a recovery from the pandemic recession which has been extremely, marvellously rapid in comparison with the experience of the 2010s. And labor markets have also been tighter than we might have expected given this rapid growth because relief programs boosted household savings and gave workers more room to be patient in searching for jobs.

This was a true shock to the economic system. And it has been one which has contributed to the emergence of categories of work which both provide mass employment and pay decent wages. This includes jobs all across the economy’s logistical apparatus, but the most visible component is employment at Amazon. The retailer now employs 1m people or so, and starting pay in logistics jobs is $18 an hour. That’s not a massive income, but to the extent that Amazon continues hiring it serves as something of a wage floor: one which could at least potentially lead to significant change across the lower rungs of the wage distribution. Moving forward, it may be the case that in local labor markets which include Amazon, employers can pay a little less than Amazon wages for more pleasant work, or they can pay as much or more as Amazon, or they can go without labor.

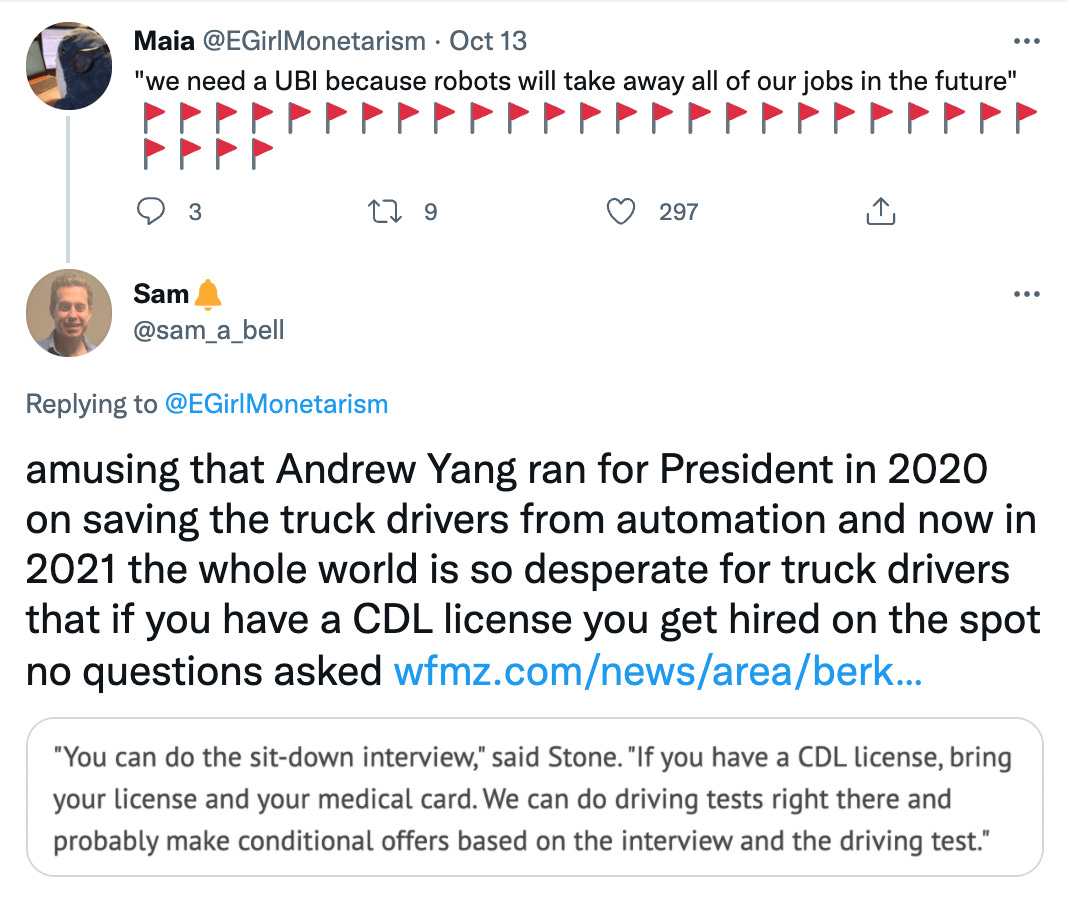

This development has produced a certain amount of gloating on the part of people who spent the 2010s fighting against arguments that labor markets were terrible because robots were taking all the jobs.

This gloating is entirely understandable and justified; the biggest problem workers faced in the 2010s, to an overwhelming degree, was a shortfall in demand. Arguments that other things were more important often had the effect of excusing Congress and the Federal Reserve from not doing much more to facilitate a rapid recovery. Even before the pandemic, the demand-obsessives’ views were being vindicated, as unemployment kept falling while the recovery continued: demonstrating that there were still plenty of jobs to be had when spending conditions permitted. And the macro experiment of the past 18 months closes the case.

Now, one funny thing about the arc of the macroeconomic storyline, for me at least, is that my book was often characterized as being a part of the whole “robots are taking our jobs” camp. It wasn’t. The book actually argues that abundant, cheap labor discouraged firms from investing in labor-saving and/or -augmenting technologies, and thus contributed to weak productivity growth. The implication of this argument, though, was that if ever we found ourselves in a situation like the current one, where the economy is once again providing mass employment at decent wage rates, then what should quickly follow, in short order, is a wave of investment in labour-augmenting and/or -saving technologies, which ought to boost productivity across the economy as a whole, but which should also act to restore conditions of labor abundance.

That argument might be wrong. If it is, and hiring of logistics workers without college degrees continues to climb for years into the future even as wages keep rising, then I’ll have egg on my face and that will be that. But we don’t know that the argument is wrong, and it seems to me that as people have their chuckles at Andrew Yang for saying that we need a universal basic income because of the robots, it might also be worth thinking about how things are likely to develop from here.

How likely is it that these jobs will continue to be performed by people? Admittedly, some logistics work is more vulnerable to automation over the near term than other sorts; warehouse jobs strike me as being particularly vulnerable while replacement of truck drivers is going to take some more time. But robotics technology has improved quite a lot in recent decades, and these big companies can’t be pleased to be shouldering large wage bills. It’s not just the wages, either. Tight labor markets increase worker bargaining power and improve the climate for the exercise of collective labor power. That annoys people.

But workers, especially those without degrees, have had a generally crummy time of things over the past few decades. It seems unreasonable, to me, to ask them not to use whatever bargaining power they have when they actually have some. But if you don’t like it when workers do this, and you think it would be better, on the whole, if employers faced no resistance when they seek to introduce new labor-saving technologies, then what’s your plan? What’s the thing that reduces workers’ anxiety about job loss and ensures that they have a decent income after robots replace them?

To ground the discussion a little here: as ambitious as policy has been over the past 18 months, Washington is clearly not about to enact a universal basic income. If the Democrats tried to, they’d find themselves facing more opponents within the party than just Manchin and Sinema. Beyond this Congress, it’s hard to know which is less likely: a Republican backed UBI, or another Democratic trifecta within the next 20 years.

That aside, let’s think ahead a bit. If the Fed doesn’t overreact to inflation and other events don’t blow up the recovery, then this labor market has some room to run. Workers at the bottom of the distribution are getting better money, which should support continued demand growth, which should keep the economy humming, which should prevent the emergence of lots of new slack—for now. One thing about making big investments to change up your operations is that it requires labor, so even if big firms start investing in new and less labor-intensive way of doing things, those investments will themselves help to maintain full employment.

But maybe not for all that long. One important piece of the puzzle here is that in many industries we already have in place business models that use less labor more productively, but which have not yet become dominant because broader conditions haven’t been sufficiently encouraging. So right now, in much of the country, you can just order your groceries online and have them delivered. If most people did this, then you could service large markets at mega grocery warehouses which relied on a mix of machine and human sorting, and in which the amount of labor which goes into completing a grocery sale is considerably smaller than is now the case. But I like going to the grocery store myself and picking out my own produce and what have you, and so I don’t order my groceries online.

As Amazon hires up all available labor, however, the experience one has shopping in person deteriorates. You go in on a Sunday afternoon and the check-out lines are horrendous because there are only two lanes open, staffed by three toddlers in a trench coat and a hatrack wearing a wig. Now shopping in person is less attractive. The stores could clear the lines by raising prices and hiring more people, but then shopping in person becomes less attractive because of the cost. If a large share of the grocery-store market were to shift to a delivery model, then that would be annoying to people who are used to doing things the old way. On the other hand, productivity within the sector would soar. And unless this rise in productivity led to a simply enormous surge in the quantity of groceries ordered per person (and maybe not even then) labor needs within the industry would decline.

Or take dining out. Dining out is great! Many people are happy to pay lots of money for a nice dining-out experience. But an awful lot of food-service establishments offer food at relatively low prices and depend upon labor which earns low wages. If these establishments can’t attract customers at higher prices and can’t afford to pay Amazon-level wages given their margins, then the quality of the dining-out experience will decline substantially and alternatives—like ordering in—will capture more of the market. It is easier in this case to see how productivity increases in food-service industries might yield offsetting increases to employment, by displacing more meals made at home. But dining out accounts for a lot of employment of workers without college degrees, and changes in business models threaten to eliminate a lot of those jobs: even if there are no robots involved.

An economist might say that these are examples of partial-equilibrium thinking: that if you look at the economy as a whole, rather than taking one market at a time, then you see that productivity-boosting changes to industry boost real incomes, which end up being spent somewhere, creating new jobs in the process. But we haven’t even gotten to the point, yet, at which Amazon uses automation to displace vast numbers of workers. And more broadly, the possibility that my book raised was that the technological capacity to automate the work of large swathes of the labor force has been building over time but hasn’t materially affected labor markets yet because there’s been no incentive to make use of it. In that sense, the potential to automate was a lot like the potential to work remotely; it’s been rising, but there hasn’t been a precipitating event to trigger its deployment. Now there has been. And it could be the case that as these technologies get deployed they improve, and firms get better at using them, and they begin to intrude into parts of the economy where previously their adoption had not been particularly economical. If that’s the case, then suddenly a lot of the automation alarmism of the 2010s becomes entirely justified. And maybe we’ll wish we had a UBI in place.

Alternatively, industry shake-ups and the occasional adoption of labor-saving methods and technologies begin to undercut the earning power that workers enjoy, and after a glorious few years wage growth decelerates. As it does, and the share of purchasing power held by those with a high propensity to spend declines, the old macroeconomic malaise sets in again. Perhaps we look back at this episode as a case in which there was a sharp rise in the level of productivity, but not a sustained period of rapid productivity growth. (Maybe that makes it the second such episode in recent memory.) And in that case we might still wish that we had a UBI, because this experience will have made clear that giving people money, by making the macroeconomic engine go again, was the thing that unlocked this period of good times for workers.

Or maybe neither of those things happen. That is also a possibility. But I think it is worth reflecting on the fact that while the current labor-market boom demonstrates that weak demand was the thing that made the 2010s so crummy, it also creates the conditions which might make those alternative theories about the 2010s, which were wrong then, right.