Two quick thoughts about Amazon

About Amazon, two quick thoughts

Amazon has been on a hiring binge right through the pandemic, for fairly obvious reasons. Globally, the Washington Post reports, Amazon payrolls have swelled by about 500,000 workers since the beginning of last year. That means it now employs about a million people, and it remains as eager to hire as ever; it is looking, for instance, to tack on another 125,000 or so workers in the months ahead.

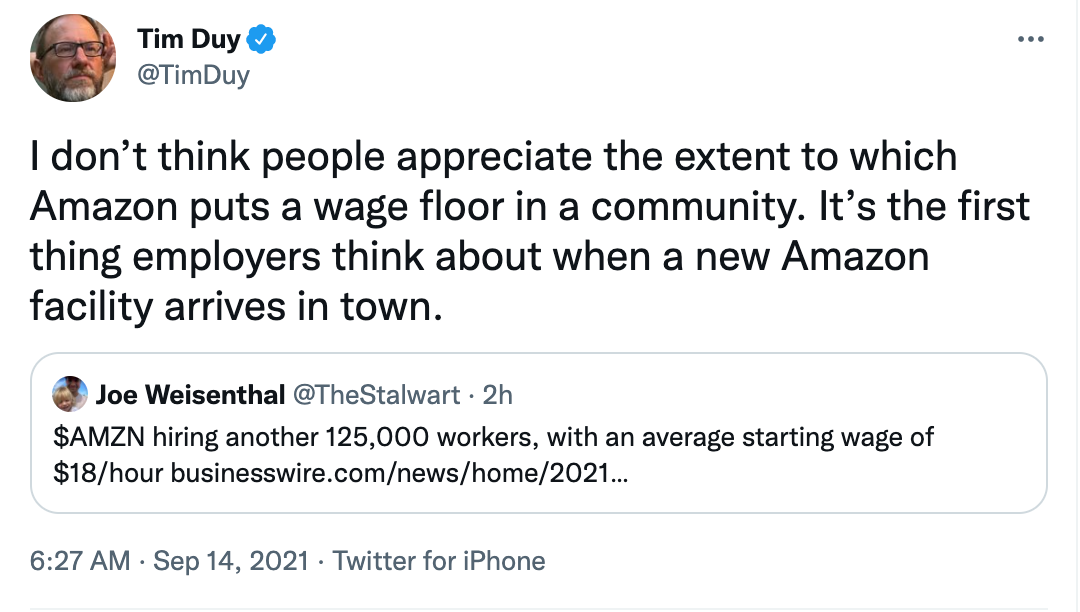

The overwhelming majority of these jobs are on the logistics side: in Amazon warehouses and delivery trucks. And importantly, Amazon is putting up wages as it hires. From today, the starting pay rate for new workers will be $18 an hour. Amazon is also paying signing bonuses in some parts of the country and says more wage hikes could be on the way.

This seems like a big deal in a country where the official federal minimum wage remains a paltry $7.25 an hour, and in which stagnant pay and high inequality have been serious problems for several decades now. Amazon is changing the game:

I’ve been thinking about this lately in the context of the ongoing debate about the meaning and likely trajectory of (modestly) high inflation. Over the past year, consumer prices have risen by 5.2%, substantially above the Fed’s 2% target. Price increases in a few outlier sectors are responsible for a lot of that, and inflation now seems to be decelerating, but underlying inflation has nonetheless run a bit hot and may well continue to do so for the next year or so as Delta ebbs and people start spending more on services once again. What has this to do with Amazon? Well, one might say that rising wages at Amazon are one early indicator of a wage-price spiral (in which higher wages force firms to raise prices which then encourage workers to demand higher wages) but that, I think, would be the wrong interpretation. Amazon is relevant to the inflation conversation for a different reason.

Why is Amazon able to pay high wages? Because it’s profitable, broadly speaking, but more narrowly: because each additional worker generates net benefits for the firm. That is, Amazon is finding ways to use workers productively, such that it can afford to pay a very high wage and nonetheless make a lot of money. Its retail business is on the whole much more productive than traditional retail, and is also experiencing productivity growth which outpaces that in other parts of the retail world. Labor productivity among nonstore retailers rose about 20% (!) from 2019 to 2020, which is more than twice the 8% rate of labor-productivity growth experienced by the retail industry as a whole.

The reallocation of workers toward Amazon and away from less productive work should generate benefits for the broader public. It should mean that consumers can get more for their money, which is to say that it ought on the whole to be disinflationary, although that effect may be difficult to discern, especially for consumers, amid other upward price pressures relating to production disruptions and the soaring cost to ship goods overseas.

It means something else for all the firms trying to compete with Amazon for workers, however. If you are a local retailer or a fast-food joint or a lawn-service company or what have you, and Amazon is hiring everyone who applies at $18 an hour, then you’re in kind of a tight spot. You may be able to pay less if the work you’re asking people to do is less onerous than work in an Amazon warehouse (on which more in a moment) but not all that much less. In 2019, the median hourly wage for 13m food prep workers was $11.65, was $13.62 for the roughly 4m grounds cleaning and maintenance workers, was $14.24 for the 14m or so people working in sales jobs, and so on. These are median wages, meaning that half of those working in each sector are paid less than that amount. For many of these folks, taking a job at Amazon means getting a raise of as much as 50%, which is a lot.

So what happens to all those businesses which have been relying on low-wage labor? They may try to get by with fewer workers, which will often mean a deterioration in the quality of the services provided to customers. If that doesn’t work then they may put up prices in order to pay higher wages so that they can get the workers they need. And at some point, many businesses may simply become non-viable. If lawn-service companies are cheap, then many households will pay for lawn services; if they’re not, then many households will mow their own lawns. Many business models which make sense with pay at $8 an hour just won’t when the going wage is twice that level.

That, it’s worth pointing out, is ok! It’s ok that some kinds of labour disappear as wage rates rise, and it’s ok when an increase in productivity in some sectors leads to a broad rise in the cost of living. This is, in fact, a fundamental feature of the process of economic development. We make adjustments for purchasing power parity when comparing real living standards across countries because in-person services, like haircuts, for which productivity doesn’t vary much across countries nonetheless cost a lot more in rich countries thanks to the overall higher level of productivity in those rich countries: high wages in the high-productivity sectors raise pay rates across the labor market as a whole. This effect also means that the optimal inflation rate in a fast-growing developing economy is meaningfully higher than in a mature economy.

Which is not to say that high prices and a declining quality of service at many businesses is a painless experience for all involved. It’s very unpleasant for the people operating those businesses, and it’s also a drag for their patrons. It was really annoying for wealthy people in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, when rising pay for factory workers meant that a large household staff was no longer affordable. Neither should we take for granted that all of the increased price pressures can be chalked up to such effects and should thus be tolerated by the Fed. But to the extent that higher inflation reflects a process of reallocation toward fast-growing high-productivity sectors—and given what we’re observing with hiring and pay at Amazon, this is clearly happening to some extent—it is on the whole a good thing.

***

But while we’re on the subject, it seems worth asking: is Amazon paying efficiency wages? An efficiency wage is one which is above the market-clearing level: that is, a higher wage than a firm needs to pay in order to attract enough workers to fill its available positions. Why would a firm pay more than it needs to?

The classic example of this practice in action is the $5 a day wage introduced by Henry Ford in 1914. Ford didn’t pay high wages out of the goodness of his heart. He did it, rather, to reduce turnover in his factories. Working on a Ford assembly line sucked. It was relentless but monotonous work: doing the same small task, over and over, on a pace which was determined by the bosses. Ford could pay a market wage and find a worker to fill an opening, but given the unpleasantness of the job the worker might soon say to hell with it, which meant more hassle for the company getting a replacement in.

Ford’s solution was to pay a wage well above the market rate. This likely had a direct effect on the morale of workers in his plant, but it also induced an excess supply of applicants: which meant that if you got tired of the work and quit you couldn’t just waltz back up to the plant door and expect to be rehired the next time you wanted to earn a wage higher than that on offer at other employers. The result, then, was a reduction in turnover and absenteeism and, seemingly, happier and more conscientious workers.

I don’t know how work in an Amazon warehouse compares with that in an early 20th century Ford factory, but it is clearly arduous and unpleasant:

The company tracks productivity with computers that show employees how many items they’ve stowed, picked or packed in an hour. Employees have complained over the years about the pressure to “make rate.” Missing those targets can lead managers to write up workers, a blemish on their record that can make it difficult to advance and can even lead to firings.

While other warehouse companies have used performance metrics, Amazon has aggressively digitized the effort and rolled it out on a massive scale...

Critics have said that Amazon’s productivity metrics are too onerous, leading workers to injure themselves. A Post investigation of work-related injury data from the Occupational Safety and Health Administration in June found that since 2017, Amazon reported a higher rate of serious injury incidents that caused employees to miss work or be shifted to light-duty tasks than at other warehouse operators in retail.

To be clear, the fact that Amazon is boosting productivity and pay doesn’t make it ok for the firm to engage in unsafe working practices, or to terrorize workers and deny them bathroom breaks, or what have you. It’s also possible that these are not in fact efficiency wages. They may be just high enough to compensate workers for the arduous nature of the work, or they could be a PR play intended to fend off regulation. I’m not sure whether there is an excess pool of applicants for Amazon jobs, which would be consistent with an efficiency wage story, or whether Amazon is simply hiring every living soul it can.

But it’s an interesting thing to think about. Amazon isn’t a bad analog for Ford in any number of ways...